Especialidades JA/Liderazgo en la naturaleza - Avanzado/Respuestas

| Liderazgo en la naturaleza - Avanzado | ||

|---|---|---|

| Asociación General

|

Destreza: 3 Año de introducción: 1976 |

|

Requisitos

1

Para consejos e instrucciones, véase Plantas silvestres comestibles.

Para consejos e instrucciones, véase Liderazgo al aire libre.

Para consejos e instrucciones, véase Liderazgo en la naturaleza.

Para consejos e instrucciones, véase Vida primitiva.

2

3

4

4a

4b

4c

4d

4e

4f

5

6

6a

When travelling over glaciers, crevasses pose a grave danger. These giant cracks in the ice are not always visible as snow can be blown and freeze over the top to make a snowbridge. At times snowbridges can be as thin as a few inches. Climbers use a system of ropes to protect themselves from such hazards. Basic gear for glacier travel includes crampons and ice axes. Teams of two to five climbers tie into a rope equally spaced. If a climber begins to fall the other members of the team perform a self-arrest to stop the fall. The other members of the team enact a crevasse rescue to pull the fallen climber from the crevasse.

6b

Dangers in mountaineering are sometimes divided into two categories: objective hazards that exist without regard to the climber's presence, like rockfall, avalanches and inclement weather, and subjective hazards that relate only to factors introduced by the climber. Equipment failure and falls due to inattention, fatigue or inadequate technique are examples of subjective hazard. A route continually swept by avalanches and storms is said to have a high level of objective danger, whereas a technically far more difficult route that is relatively safe from these dangers may be regarded as objectively safer.

In all, mountaineers must concern themselves with dangers: falling rocks, falling ice, snow-avalanches, the climber falling, falls from ice slopes, falls down snow slopes, falls into crevasses and the dangers from altitude and weather. To select and follow a route using one's skills and experience to mitigate these dangers is to exercise the climber's craft.

6c

Compacted snow conditions allow one to progress on foot. Frequently crampons are required to travel efficiently over snow and ice. Crampons have 8-14 spikes and are attached to a mountaineer's boots. They are used on hard snow (neve) and ice to provide additional traction and allow very steep ascents and descents. Varieties range from lightweight aluminum models intended for walking on snow covered glaciers, to aggressive steel models intended for vertical and overhanging ice and rock. Snowshoes can be used to walk through deep snow. Skis can be used everywhere snowshoes can and also in steeper, more alpine landscapes, although it takes considerable practice to develop strong skills for difficult terrain.

6d

Water travel means travelling by means of some sort of boat, be it a sailboat, motorboat, rowboat, canoe, or kayak. In all cases, it is important that every person have access to a Personal Flotation Device (PFD), also known as a life jacket. See the answers to the following honors for more information:

7

The wilderness, though filled with beauty, is an inherently dangerous place. The dangers presented by the wilderness come in many forms, including wild animals, weather, flash flooding, injuries, falls from high places, falling trees, etc. This list could extend for many pages. Compounding these dangers is the fact that any incidents which require medical attention will have to be dealt with long before a victim can be transported to a hospital. So while it is important that one's skills match the situations likely to be encountered, it is also important that the leader stay in touch with The Almighty.

Get in the habit of communing with Him on a regular basis. Consult Him on all major decisions. But most of all, understand that He will be with you as you face any danger. For he will command his angels concerning you to guard you in all your ways. - Psalm 91:11, NIV.

8

The survival of the wilderness is threatened by man. Our continual overuse of resources drives people to clear forests at a rate much faster than they can regrow. The best protection the wilderness has is that we change our lifestyles so that they are sustainable. Try walking or riding a bike instead of jumping mindlessly into the car. Buy a fuel-efficient car instead of a gas-guzzler. Learn how to repair things instead of throwing them away and replacing them (this is a lot easier when you buy quality items rather than "disposable" ones). Pay attention to how the things you consume are made. Remember that it takes more energy to feed corn to beef cattle than it does for you to eat the corn yourself. By controlling consumption, we can slow the rate at which the wilderness disappears.

Many governments have recognized this problem and have responded by setting aside protected wilderness areas. These are the areas you are likely to enjoy when you engage in the activities outlined in this honor, so it is imperative that you do everything you can to preserve them. Wilderness lovers frequently quote two mottoes related to the preservation of the wilderness. The first is "Take only pictures, leave only footprints." The second is "Pack in, pack out." The first of these is covered sufficiently in the Camping Skills honors that lead up to this one, so we will not rehash it here. The second relates to the practice of not leaving anything in the wilderness that you brought in with you. There are many old (and out-of-date) woodcraft guides that advise burning your trash, and burying what you cannot burn. Modern practice dictates that if you had the space in your pack to bring your trash into the wilderness with you, you will also have room in your pack to bring right back out. Do not leave your trash behind.

9

- Backpacking

- Camping Skills I

- Camping Skills II

- Camping Skills III

- Camping Skills IV

- Fire Building & Camp Cookery

- First Aid

- Hiking

- Orienteering

10

Debris Hut

These instructions for making a debris hut were taken from U.S. Army Field Manual, No. 21-76, Survival.

For warmth and ease of construction, this shelter is one of the best. When shelter is essential to survival, build this shelter.

To make a debris hut:

- Build it by making a tripod with two short stakes and a long ridgepole or by placing one end of a long ridgepole on top of a sturdy base.

- Secure the ridgepole (pole running the length of the shelter) using the tripod method or by anchoring it to a tree at about waist height.

- Prop large sticks along both sides of the ridgepole to create a wedge-shaped ribbing effect. Ensure the ribbing is wide enough to accommodate your body and steep enough to shed moisture.

- Place finer sticks and brush crosswise on the ribbing. These form a latticework that will keep the insulating material (grass, pine needles, leaves) from falling through the ribbing into the sleeping area.

- Add light, dry, if possible, soft debris over the ribbing until the insulating material is at least 1 meter thick--the thicker the better.

- Place a 30-centimeter layer of insulating material inside the shelter.

- At the entrance, pile insulating material that you can drag to you once inside the shelter to close the entrance or build a door.

- As a final step in constructing this shelter, add shingling material or branches on top of the debris layer to prevent the insulating material from blowing away in a storm.

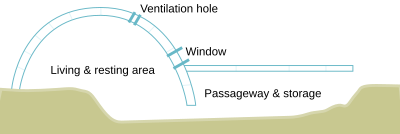

Snow Shelters

Another option is to build an igloo, build a snow fort, hollow out a snow drift, or build a Quinzhee (which is made by first making a pile of snow, and then hollowing it out). All of these require a considerable expenditure of energy, and it is imperative that the workers not soak their clothing with sweat while working. If you find you are sweating, remove a layer or two.

When referring to a snowhouse, igloos are shelters constructed from blocks of snow, generally in the form of a dome. Although igloos are usually associated with all Inuit, they were predominantly constructed by people of Canada's Central Arctic and Greenland's Thule area. Other Inuit people tended to use snow to insulate their houses which consisted of whalebone and hides. Snow was used because the air pockets trapped in it make it an insulator. On the outside, temperatures may be as low as −45 °C (−49.0 °F), but on the inside the temperature may range from −7 °C (19 °F) to 16 °C (61 °F) when warmed by body heat alone.

The snow for a quinzhee need not be of the same quality as required for an igloo. Quinzhees are not usually meant as a form of permanent shelter, while igloos can be used for seasonal and year round habitation. The construction of a quinzhee is slightly easier than the construction of an igloo, although the overall result is somewhat less sturdy and more prone to collapsing in harsh weather conditions. Quinzhees are normally constructed in times of necessity, usually as an instrument of survival, so aesthetic and long-term dwelling considerations are normally exchanged for economy of time and materials.

To build a quinzhee, begin by making a large pile of snow about 2 meters![]() high, and 3 meters

high, and 3 meters![]() in diameter. You can optionally start the pile with large, easily removed items, such as a couple of backpacks. This will make it easier to hollow out the pile, but if you find yourself in need of something in your pack before the pack has been freed, you will have to wait. Once the pile has been built, let it set for an hour or two. This allows the snow to undergo a process called sintering which binds the ice crystals together. Before you begin hollowing it out though, find several sticks 20-30 cm

in diameter. You can optionally start the pile with large, easily removed items, such as a couple of backpacks. This will make it easier to hollow out the pile, but if you find yourself in need of something in your pack before the pack has been freed, you will have to wait. Once the pile has been built, let it set for an hour or two. This allows the snow to undergo a process called sintering which binds the ice crystals together. Before you begin hollowing it out though, find several sticks 20-30 cm![]() long. Break them until they are all the same length, then jam them straight into the pile until they disappear. These will help you gauge the thickness of the walls as you hollow out the center. Then, using a shovel, start removing snow. Dig a tunnel first, then enlarge it. Stop digging in an area when you find one of the gauge sticks inserted previously. The last step it to create a couple of ventilation holes. These should be small tunnels about 5 cm

long. Break them until they are all the same length, then jam them straight into the pile until they disappear. These will help you gauge the thickness of the walls as you hollow out the center. Then, using a shovel, start removing snow. Dig a tunnel first, then enlarge it. Stop digging in an area when you find one of the gauge sticks inserted previously. The last step it to create a couple of ventilation holes. These should be small tunnels about 5 cm![]() in diameter, positioned not at the top of the quinzhee, but not far from it either.

in diameter, positioned not at the top of the quinzhee, but not far from it either.

In any of these structures, it is important to make the resting area higher than the floor. This is because cold air sinks, so the coldest place inside a snow shelter will be on the floor.

11

References

- Categoría: Tiene imagen de insignia

- Categoría:Libro de Respuestas de Especialidades JA/Especialidades

- Categoría:Libro de Respuestas de Especialidades JA

- Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Skill Level 3/es

- Categoría: Libro de respuestas de especialidades JA/Especialidades introducidas en 1976

- Categoría:Libro de Respuestas de Especialidades JA/Asociación General

- Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Recreation/es

- Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Recreation/Primary/es

- Categoría:Libro de Respuestas de Especialidades JA/Etapa 25

- AY Honors/Prerequisite/Edible Wild Plants/es

- AY Honors/See Also/Edible Wild Plants/es

- AY Honors/Prerequisite/Outdoor Leadership/es

- AY Honors/See Also/Outdoor Leadership/es

- AY Honors/Prerequisite/Wilderness Leadership/es

- AY Honors/See Also/Wilderness Leadership/es

- AY Honors/Prerequisite/Wilderness Living/es

- AY Honors/See Also/Wilderness Living/es