Difference between revisions of "AY Honors/Braille/Answer Key"

(+ Kenneth Jernigan quote) |

|||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

==2. Discuss who needs a tactile reading system and what is needed to read it.== <!--T:4--> | ==2. Discuss who needs a tactile reading system and what is needed to read it.== <!--T:4--> | ||

People who are legally blind, who have a visual acuity of 20/200 or worse with corrective lenses, are typically unable to read large print or even the largest letter on an eye chart placed 20 feet away. | People who are legally blind, who have a visual acuity of 20/200 or worse with corrective lenses, are typically unable to read large print or even the largest letter on an eye chart placed 20 feet away. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Here’s an additional definition from Kenneth Jernigan, longtime leader of the National Federation of the Blind: "One is blind to the extent that the individual must devise alternative techniques to do efficiently those things which he would do if he had normal vision" <ref name="Kenneth Jernigan quote">[https://nfb.org/images/nfb/publications/fr/fr19/fr05si03.htm A Definition of Blindness, Kenneth Jernigan]</ref>. | ||

===a. Find an eye exam chart and follow the directions to test your vision. What constitutes good vision as opposed to legal blindness?=== <!--T:5--> | ===a. Find an eye exam chart and follow the directions to test your vision. What constitutes good vision as opposed to legal blindness?=== <!--T:5--> | ||

Revision as of 13:38, 29 June 2019

Braille

Approval authority:

Category:

Skill Level:

Year of Introduction:

![]()

Contents

1. What is a tactile reading system?

A method of printing meant to be read without sight, typically with the fingers.

2. Discuss who needs a tactile reading system and what is needed to read it.

People who are legally blind, who have a visual acuity of 20/200 or worse with corrective lenses, are typically unable to read large print or even the largest letter on an eye chart placed 20 feet away.

Here’s an additional definition from Kenneth Jernigan, longtime leader of the National Federation of the Blind: "One is blind to the extent that the individual must devise alternative techniques to do efficiently those things which he would do if he had normal vision" &.

a. Find an eye exam chart and follow the directions to test your vision. What constitutes good vision as opposed to legal blindness?

Note: This activity is not designed to diagnose visual issues. Direct students to follow up with their eye health provider regarding any vision concerns.

Additionally, a reasonably high epicritic sensitivity, the ability to distinguish between small variances, is helpful when reading braille. The majority of people who learn to use braille will use their fingers, though some can read it visually, and others may use another part of the body, such as the tongue when fingers lose epicritic sensitivity or if you lose fingers all together.

b. Using a multisensory activity, evaluate your epicritic sensitivity.

Activity: Do You Have Epicritic Sensitivity?

An easy way to test is to feel textures on various surfaces.

Instructors: Set up an area with commonly available items, such as sandpaper, a spiral notebook, LEGO bricks, plain and textured papers, etc. Students can test their ability to feel different textures to assess their epicritic sensitivity.

Note: Even if a person has epicritic sensitivity, it takes years for an individual to learn braille. The helpful first step is to recognize this sensitivity, followed by practice recognizing braille cells as meaningful content. Much the same way sighted children take years to learn to read and write in their native language, the acquisition of braille literacy also takes time, training, and lots of practice.

3. Briefly discuss the history of tactile reading systems, including the following points:

a. Who was Louis Braille?

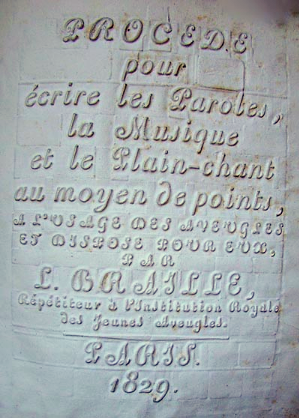

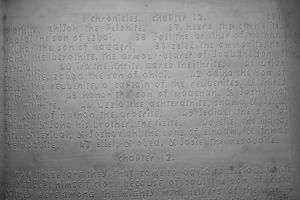

Louis Braille was a French educator, inventor, and musician who created braille because he wanted to bridge the gap between people who are blind and people who are sighted. Louis was born in 1809 and was blinded in both eyes as the result of a childhood accident. He attended the Institut National des Jeunes Aveugles (Royal Institute for Blind Youth), which was the first specialized school in the world for people who are blind. Louis learned to read the Haüy system of raised print letters in Latin. The printing method for the Haüy system utilized wet paper and copper wire. Because of the complexity of printing Haüy, this system was virtually unusable for people who are blind as a writing system, in addition to being difficult to read.

A frustrated Louis was determined to invent a system of reading and writing that could bridge the gap in communication. "Access to communication in the widest sense is access to knowledge, and that is vitally important for us if we [the blind] are not to go on being despised or patronized by condescending sighted people. We do not need pity, nor do we need to be reminded we are vulnerable. We must be treated as equals — and communication is the way this can be brought about." - Louis Braille, 1841&

In 1821, Louis learned of a communication system devised by French Army Captain Charles Barbier, called “Night Writing,” which was comprised of a cell of up to 12 dots arranged in two columns. Part of what made this system appealing was that readers of this system could also write it without the complicated equipment other tactile fonts required at that time. Haüy, for example required copper wire and damp paper, in addition to the space to dry it.

Louis adapted Captain Barbier’s code into cells of raised dots, two across and as many as three high, completing the majority of this work by age 15. Although acknowledged by many as an ingenious and useful system, braille was not adopted by the Royal Institute for Blind Youth, and later the world over, until two years after Louis’ death at age 43.

b. List some of the tactile reading systems that competed with braille in “The War of the Dots.”

Until 1932, many tactile reading systems competed with braille, especially Moon type, New York point, and variations of braille that assigned the most frequently used letters the fewest dots. This time is referred to as “The War of The Dots.” There were so many systems, and so many changes being made to the existing systems, that in 1919 a speaker at a national convention said, "If anyone invents a new system of printing for the blind, shoot him on the spot."

Below is a list of some of the more popular systems. The list below is not exhaustive.

- Haüy: Named for Valentin Haüy, the founder of the first school for the blind in Paris, France. This is the oldest known “font” for the blind. These raised letters were more artisan than practical.

- Gall: Named for Scottish clergyman and inventor James Gall, whose “triangular alphabet” used both capital and lowercase letters.

- Boston Line Type: A raised font developed by Samuel Gridley Howe, the founder of the New England School for the Blind (later, the Perkins School for the Blind) in Massachusetts, United States. This font was styled to be easier to feel and differentiate letters.

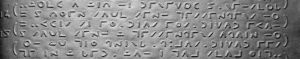

- Moon Type: Created by William Moon, who lost much of his eyesight from scarlet fever. This font is partially based on letter shape and is somewhat alien in appearance.

- New York Point: Unlike braille, which is three dots high and two dots wide, New York Point, which was developed by William Bell Wait, was two dots high and three or four dots wide. It also had configurations for capital letters, word endings, and blends: “ing,” “ou,” “ch,” “sh,” “th,” “wh,” “ph,” and “gh.”

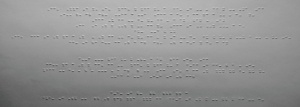

4. Explain how braille systems are adapted to different languages.

Unified English Braille (UEB for short, also referred to simply as braille) is a braille code that has standardized access to literary and technical material, regardless of regional dialect. As of 2013, the majority of English-speaking countries have adopted UEB. Before the international agreements to use UEB, each country used its own variations of letters, contractions, and codes for math and programming. UEB allows for easier communication among braille users, as well as with them to non-users. For example, the “@” symbol, used for email, Twitter, etc. is considered a staple in modern culture. However, there was not a standard way to represent that symbol in braille without switching to computer code braille, which was impractical to do for one symbol. UEB also has characters for italics, bold, accents, and more. This gives the reader a truer sense of what was originally written for print.

In UEB there are four grades that utilize varying levels of contractions and abbreviations. All grades have been updated to some degree from the previous versions of braille.

Note: There are braille codes for just about every language, so people can read and write in the language they speak. While many do follow the principles of assigning values of a linear script (print) to braille, some do not. For example, there are braille scripts which don't order the codes numerically at all, such as Japanese braille and Korean braille, which are based on more abstract principles of syllable composition.

| Grade 1 | This is very close to a 1:1 letter representation |

|---|---|

| Grade 2 | This is a moderately contracted code and the most like the previous version of braille |

| Grade 3 | This is a personal shorthand for taking notes and typically NOT something that would be used to communicate with anyone but yourself |

| UEB | This last version does not have grade number and is simply called UEB. This grade is highly contracted and is the goal for an international English standard. |