Especialidades JA/Pantanos y ciénagas/Respuestas

Nivel de destreza

2

Año

2014

Version

08.06.2024

Autoridad de aprobación

Asociación General

1

2

3

4

5

Bogs and Fens are both sources of peat and have a floating mat of vegetation. The major difference has to do with the water source. Bogs are closed systems that have no connection to groundwater sources, Fens are open systems that depend on a groundwater source (springs). Fens are less acidic, have more nutrients and support a more diverse community of plants and animals. For a fen, the mat of vegetation is composed of herbs and grasses such as Tussock Grass.

6

- Exposed leaves are covered in waxy material, have thick woolly hair-like fibers, or hide their pores in deep pits on the underside to conserve nutrients and to reduce toxins such as iron and manganese.

- Grow low to the ground or have slow stunted growth.

- Survive dramatic temperature differences.

- Live in acid conditions with low nutrients.

7

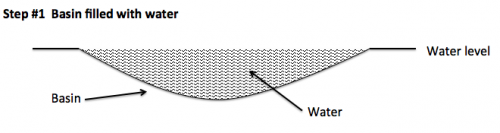

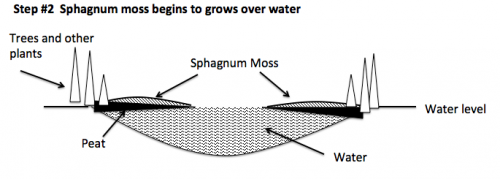

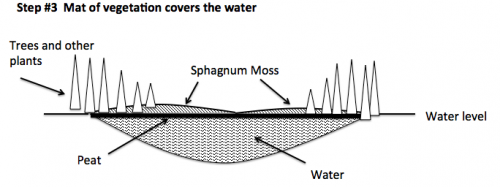

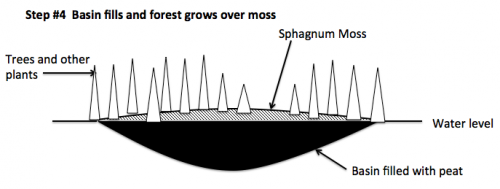

Sphagnum Moss or Peat Moss (Family Sphagnaceae) is a plant that shapes and drives bog chemistry. It has gas-filled cells that help it to float and has amazing absorption properties enabling it to hold many times its own weight in water. It grows from the top and dies just a small distance down the stem. It slowly grows out from shore eventually forming a floating mat of vegetation over any open water resulting in the sun not being able to warm the water below. When new moss forms, the old moss is pushed underwater and decays very slowly into peat. As it slowly decays, tannin and acids are released killing bacteria and removing dissolved oxygen that would otherwise cause decomposition to occur, also turning the water brown. Dead peat moss accumulates until it is many feet deep and eventually, given enough time, will reach ground level below and fill the bog completely.. Sphagnum Moss supports a variety of acid loving plants, shrubs and even trees to grow on top of its floating mass over deep water, also called bog forest. When stepped on, the mats shake, tilt and ripple causing even trees to sway. Falling into a bog can be dangerous so it is best to stay on designated boardwalks and trails.

8

Carnivorous plants trap animal prey (insects) to make up for the loss of nutrients they cannot obtain from the environment. The traps are modified leaves and may be “active” or “passive” depending on how they catch their prey.

Pitcher Plant (Passive)

These plants form a slippery, colorful cupped leaf, and have a nectar-covered lip to lure insects. When an insect slips and falls in, it is trapped by downward pointing, sharp hairs. It is slowly dissolved in the liquid in the bottom of the cup. There are some insects that thrive in the pitcher plants by having an anti-enzyme that prevents them from being digested by the plant.

9

10

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Species Account/Alces alces

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Species Account/Lycaena epixanthe

11

This is one example. You can develop your own story.

12

12a

12b

12c

12d

12e

| Tip for earning from home during the pandemic | |

| This can be done using video conferencing (or by using the writing/short video options). |

See the Video honor for instruction on making your video, and be sure to check out the Environmental Conservation and Endangered Species honors while you're researching this option.

References

- Benyus, J. M. (1989). Northwoods Wildlife, A Watcher's Guide to Habitats. Minocqua, WI: Northwood Press.

- Brock, J. P., & Kauffman, K. (2003). Butterflies of North America. New York, New York: Hillstar Editions, L.C and Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Campbell, S., Hunt, A., Kerridge, R., Lynch, T., & Wohl, E. (2011). The Face of the Earth; Natural Landscapes, Science and Culture. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press.

- Eastman, J. (1995). The Book of Swamp and Bog. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvannia: Stackpole Books.

- EcoRiskProfile. (n.d.). Retrieved from www.epa.gov: http://www.epa.gov/region1/ge/thesite/restofriver/reports/final_era/B%20-%20Focus%20Species%20Profiles/EcoRiskProfile_wood_frog.pdf

- Graham, L. E., Graham, J. M., & Wilcox, L. W. (2003). Plant Biology. In Plant Biology. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education, Inc.

- Haslam, S. M. (2003). Understanding Wetlands. New York, New York: Taylor and Francis.

- Johnson, C. W., & Worley, I. A. (1985). Bogs Of The Northeast. Hanover, New Hampshire: University Press of New England.

- Larsen, J. A. (1982). Ecology of the Northern Lowland Bogs and Conifer Forests. New York, New York: Academic Press, Inc.

- Milne, L. J., & Milne, M. (1984). The Mystery of the Bog Forest. Toronto, Canada: McClelland and Stewart Limited.

- Mitsch, W. J., & Gosselink, J. G. (1993). Wetlands: Second Edition. New York, New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, International Thomson Publishing.

- Moore, P. D. (2008). Wetlands. New York, New York: Facts on File, Inc.

- Niering, W. A. (1989). The Audubo Society Nature Guides, Wetlands. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. and Random House, Inc.

- Root, P., & Bowen, B. (2010). Big Belching Bog. Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press.